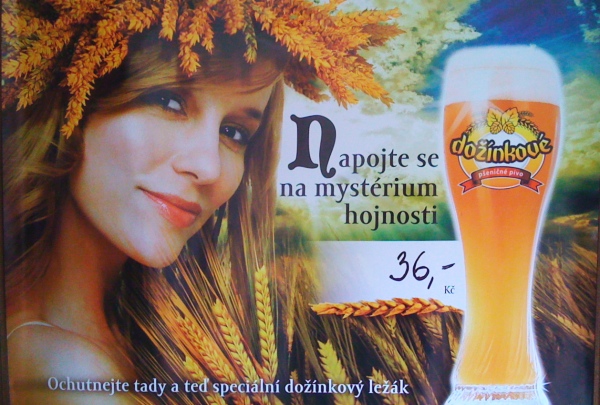

As a follow-up from last week’s post on two new wheat beers in the Czech Republic, I’ve got more details about the new Dožínkové pivo appearing at outlets of Heineken Česká republika around the country. And no, it’s not exactly from Krušovice. And it wasn’t brewed at Starobrno, either.

Tag: wheat beer

You’re walking down the street in Prague, completely minding your own, when your eye hangs on a sign announcing a new beer. What stops you is an apparent error in the picture: instead of barley, the poster is adorned with what seems to be wheat.

Called Dožínkové pivo, the Czech Republic’s newest wheat beer started to show up at pubs around the country this week. There are two surprising things about the appearance of a new wheat beer in Bohemia, not the least of which is the brewery making it. (Drumroll, please…)

You hit the road for a few days of peace and solitude in South Bohemia and what happens? A great beer that has been AWOL for years suddenly returns to the scene.

The brew in question is the very nice wheat beer from Pivovar Herold, a brewery I pass each time I drive down to my wife’s family’s summer home in Písek. As I’ve mentioned before, the history of the brewery in the town of Březnice is covered in Ludvík Fürst’s monograph “Jak se u nás vařilo pivo” (or “How we used to brew beer”). In that book, Fürst quotes documents mentioning the production of wheat beer at Březnice in the sixteenth century. When Herold reintroduced its modern wheat beers in 2002, they were the only Czech wheat beers available in bottles at the time.

Today, many — if not most — European beers are made with barley. Earlier European beers, however, were made with any number of other grains. But then came the reformers: Bavaria’s Reinheitsgebot proscribed the use of anything other than barley in 1516; in Bohemia, the great brewing scientist František Ondřej Poupě, author of “The Art of Beer Brewing” (1794), helped kill off other grains at the end of the eighteenth century, famously declaring that oats were for horses, wheat was for cakes, and only barley was fit for beer.

So before barley was the only ingredient to use, what did beers taste like? They might have been a bit like the Historisches Emmer Bier from Germany’s Riedenburger brewery, made with malted emmer, einkorn and spelt (all early domesticated forms of wheat), as well as barley and modern wheat.

One of the cool Bavarians to show up at last year’s Christmas Beer Markets was Schneider’s Aventinus, an amber wheat beer that kicks like a Doppelbock, blending plummy stewed fruit with Weißbier spice and plenty of alcoholic wallop.

One of the cool Bavarians to show up at last year’s Christmas Beer Markets was Schneider’s Aventinus, an amber wheat beer that kicks like a Doppelbock, blending plummy stewed fruit with Weißbier spice and plenty of alcoholic wallop.

Right now, Richter Brewery in Prague has something similar on tap: a polotmavý (half-dark, meaning amber) Weißbier. It’s brewed at a conventional 13° with about 5% alcohol, versus 18.5° and a massive 8.2% for the brawny German.

The strength might be the biggest difference between the two, as some of the flavors and aromas are quite similar. The nose of the Polotmavý Weißbier has cooked plums and chocolate and cocoa notes with just a breath of citrus acidity. In the mouth, it starts out with fairly sweet and complex fruitcake flavors before a dry finish.

Half-liters of Richter’s Polotmavý Weißbier are 35 Kč. Get one while you can.

Though the Czech Republic’s overall beer output rocked an all-time high of over 20 million hectoliters (12 million barrels) last year, growth is slowing as it hits the top of the arch. One category is still rocketing forward, however: nonalcoholic beer. In 2007, production of Czech nonalcoholic beer fully doubled from the year before, hitting half a million hectoliters of fine-to-drive lager containing .5% alcohol by volume or less.

That’s quite a change from just a few years ago, when nonalcoholic beer was rarely seen. Now nearly everyone offers nealkoholické pivo in bottles, and several varieties are even available on draft, with more versions showing up every month: Svijany introduced its nonalcoholic beer in 2006; Chodovar sent out its brew in 2007. Growth appears in every corner of the country: Litovel’s nonalcoholic beer production jumped 57% in 2007; Primátor expanded its distribution of NA beer by 65% from the year before; Budvar grew its sales of nealkoholické pivo by 55% last year.

Two reasons for the pick up:

1 . The Czech Republic has a zero-tolerance policy for drinking and driving. (It might be flouted, but that is the law.)

2. Some Czech nonalcoholic beers actually taste good.