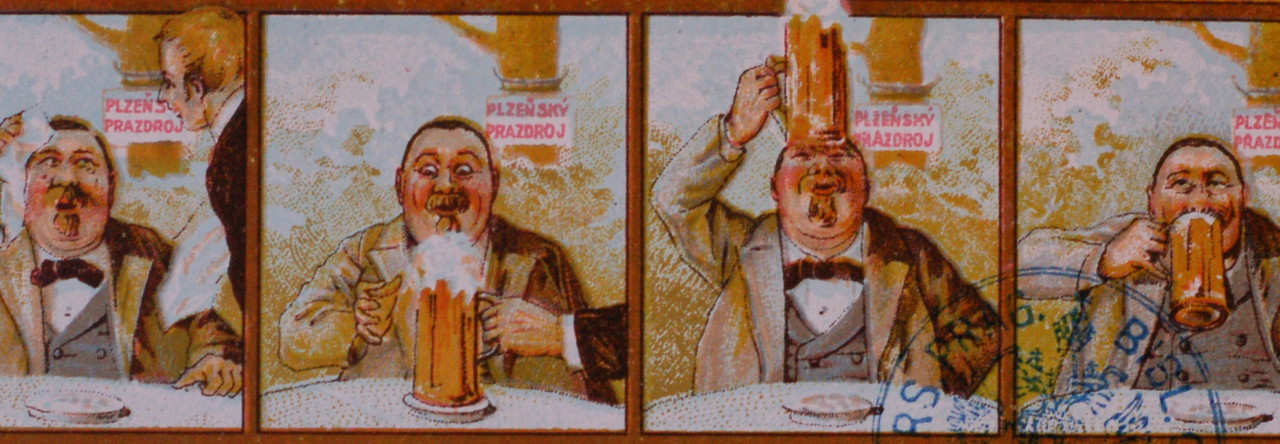

From the “Stories that Got Away” file: the great Prague pub U Medvídků is known for a couple of things. One is the never-ending supply of Budweiser Budvar rolling out in the cavernous beer hall downstairs. And for the past few years, the place has been hailed for its top-shelf — albeit tiny — brewpub upstairs, which makes limited amounts of a couple of great beers: the outstanding Oldgott lager and the extra-strong X-33 beer, a bottom-fermented beer that resembles a barley wine, both in its level of alcohol (12.6%) and its syrupy texture.

Both of those beers, however, are amber. If you wanted a pale lager — the country’s most popular style — or if you felt like a dark beer at U Medvídků, you could only have Budweiser Budvar. But that’s changed.