First brewed on October 5 of 1842 — almost 170 years ago as of this writing — the Burghers’ Brewery in Pilsen, now known as Pilsner Urquell, is one of the few breweries truly deserving the term “legendary.” However, not all of those legends are true, especially when it comes to the early days of the original Pilsner.

Did the original recipe really use Saaz hops? Has there been any variation in the type of beer that has been called Pilsner Urquell? And wasn’t the brewery founded by Germans?

The following are a few mistakes, misunderstandings and misconceptions about Pilsner Urquell’s beginnings, taken from various sources: beery talk in pubs, beer blogs, The Oxford Companion to Beer, and even my own guidebook from 2007, by which we’ll kick things off.

“The first pub to serve Pilsner Urquell in Prague started up in 1843… U Pinkasů” (Good Beer Guide Prague and the Czech Republic)

U Pinkasů certainly does claim to be the first (“první v Praze”), a boast which has even been repeated by Pilsner Urquell’s marketing department, but according to the brewery’s own chronicle, Měšťanský Pivovar v Plzni 1842–1892, the first pub to tap the beer in Prague was Karel Knobloch’s tavern U Modré Štiky, once located at the corner of Karlova and Liliova streets, which started selling Pilsner Urquell as early as the brewery’s inaugural year of 1842 — one year before U Pinkasů.

Pilsner Urquell has only ever been one beer, the exact same pale lager it is today.

This is incorrect. Even the first brewer, Josef Groll, initially put out two kinds of beer in 1842–1843, both výčepní and ležák, and about twice as much of the former as the latter (source: Měšťanský Pivovar v Plzni 1842–1892). That is to say: in addition to the familiar ležák (“lager,” in this case referring to the beer’s strength) around 12° Balling / Plato, Groll also brewed a weaker beer, probably around 10°, which has no analogue at the brewery today.

By 1907, records show that the Burghers’ Brewery was producing three different beers: an 11° lager which they called “výčepní, či zimní,” (meaning “taproom, or winter”), again with no contemporary equivalent, as well as a 12° světlý ležák, presumably most like today’s Pilsner Urquell, and “pro zámořský transport 13 stupňový exportní ležák,” or an unusual “13-degree export lager for overseas transport.” (Source: Plzeňský Prazdroj, pivo z Měšťanského pivovaru v Plzni, a brewery brochure from 1907.)

The first pilsner was created using Saaz hops (Wikipedia). Groll added generous portions of the fragrant Saaz hops to his brew (“History of Pilsner” at beer.about.com)

File this under “For What It’s Worth,” but according to Měšťanský Pivovar v Plzni 1842–1892, the hops for the first batch of beer from the Burghers’ Brewery in Pilsen — and all of the batches from 1842 until at least 1844 — were purchased from Josef Fischbach in Mnichov, near Mariánské Lázně, some 78 kilometers (48 miles) away from Žatec, the town known as Saaz in German, a place that is not considered part of the Žatec Saaz hop region today.

Legend holds that in 1840 a monk smuggled some of the precious lager yeast out of Bavaria (“History of Pilsner” at beer.about.com)

We’ve gone over this before, but to clarify once again, the historical record notes that bottom-fermenting “seed yeast (yeast, material) for the first batch and fermented wort were purchased from Bavaria” (Měšťanský Pivovar v Plzni 1842–1892). Not smuggled: purchased, without the assistance of any monk.

Even if the brewery’s own records didn’t contradict this legend, which they do, it might be helpful to remember that Napoleon secularized German monasteries and their breweries at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

The first batch of Pilsner Urquell was tapped on 5 October, or 11 November, or 25 February of 1842, depending on whom you ask.

If you ask the historical record, there’s little doubt: Měšťanský Pivovar v Plzni 1842–1892, and the 1883 Pilsen city chronicle Kniha pamětní král. krajského města Plzně od roku 775 až 1870 note that the first batch of beer was brewed on October 5, 1842, and then first tapped during the St. Martin’s Fair in Pilsen on November 11, 1842.

Bonus refutation for those who claim that Pilsner Urquell has shortened its lagering times: note the original count of just 37 days from grain to glass. That’s roughly the same amount as today, when the total brewing time is said to average around five weeks. The brewery might have shortened its lagering times at some point, but if so, it lengthened them first.

If you have ever been to the brewery in Plzeň, one thing is plainly clear, this brewery was built for volume. It was never built as a little operation that became popular and had to scale up.

Yes and no — but mostly no. The brewery was certainly built for serious production in its era, and it turned out a substantial volume in its first brewing year of 1842–1843, when it produced 6,326 věder, or about 3,580 hectoliters — 2,140 hectoliters of which was everyday výčepní, while the stronger ležák accounted for 1,440 hectoliters (source: Měšťanský Pivovar v Plzni 1842–1892). Just three years later in 1845-1846, production had already reached 5,790 hectoliters.

With that kind of growth, it’s hardly surprising that the brewery began “scaling up” almost immediately, starting its first expansion as early as 1847, when additional properties were purchased to add a total of 4,468 square meters to the brewery’s original footprint of just 1,378 square meters. An engineer from Bavaria, Mr. Unger, was hired to plan the construction of new buildings, and enough barrels to lager an additional ten batches of beer were newly purchased from Mr. Vyskočil, a master cooper in the town of Nové Strašecí, not far from Rakovník, another significant investment. Output that year grew to 6,351 hectoliters, an increase of 77% from the original production level of just four years earlier (source: Měšťanský Pivovar v Plzni 1842–1892.)

Remember, the main goal of the burghers with brewing rights was to maintain the beer market in their hometown — originally, selling beer outside Pilsen was presented only as a possibility. But by 1856, Pilsner beer was already being sold in Vienna, and by 1859 the burghers attempted to register a trademark for “Pilsner Bier,” allegedly in order to protect their brew from its early imitations. In other words, it clearly did become popular, in Pilsen and elsewhere, and the brewery most certainly was forced to scale up.

Additional expansions followed throughout the nineteenth century, including a massive renovation in 1873 which replaced the earlier buildings with a new complex of buildings that then covered 36 hectares (source: Plzeňský Prazdroj v historických fotografiích, 2005).

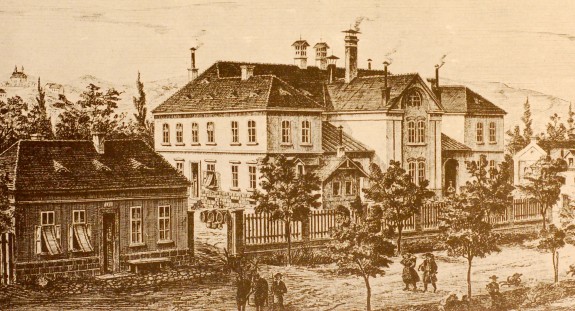

The original brewery looked quite unlike anything contemporary visitors can see, as you can tell from the picture at the top of this post, which depicts the Burghers’ Brewery as it first appeared back in 1842 — decidedly unlike the sprawling grounds of Pilsner Urquell today.

The original lager beer (Lagerbier) was invented by the German brewers Martin Stelzer and Josef Groll…

If you’re trying to locate the internet’s lunatic fringe, look first among the comments at the New York Times, like this one (#110) on a post about German identity. Martin Stelzer might have built the original brewery, but he was not a brewer. He also built the town’s Great Synagogue, but that didn’t make him a rabbi. Not any more than his blueprints for the town’s theater might have made him an actor.

For the last time, Martin Stelzer was an architect, not a brewer.

Pilsen was still a predominately German town in 1838, as it was until 1860, and it it took until 1918 for Czech speakers to become a clear majority.

It is true that most of the documentation from the brewery’s earliest days is in German. However, while German might have been the official language of the city’s government and administration, language use does not equal ethnic background. (Your humble Guide might speak French, but he is not French. Nor is he, for that matter, Czech.)

Ethnically, Pilsen appears to have always been a predominantly Czech town: before the nineteenth century, throughout the nineteenth century, and afterwards. In 1786, a commission set up by Emperor Joseph II to establish church services in the German and Czech languages found that the town of Pilsen had 5,509 Czech speakers and 938 German speakers (cited in Ottův Slovník Naučný, 1902). Thus, even before the arrival of the nineteenth century, Czechs in Pilsen outnumbered Germans there by about five to one.

That ratio seems to have remained roughly the same throughout the nineteenth century. In 1880, a census counted 38,883 citizens of Pilsen, of whom 31,600 were Czechs, with 6,827 Germans (Města a Městečka v Čechách, na Moravě a ve Slezsku, 2002). The 1900 census tallied 57,806 Czechs in Pilsen, while Germans made up 8,008 (Ottův Slovník Naučný, 1902).

However, upper-class society in Pilsen did begin to use German much more often in the first half of the nineteenth century, especially in the wake of German-language education in the schools built in Pilsen at the end of the eighteenth century. But while the Czech language was falling out of favor in many of the city’s bourgeois families, Czech remained the language of the city’s poorer classes, merchants and tradesmen (source: Dějiny Plzně v datech, 2004).

Moreover, even long before the revolutionary year of 1848, a serious effort was being made to revive the use of the Czech language among Pilsen’s upper classes, so much so that by 1847, a German speaker would complain that

..in the great city of Pilsen, where the population is mixed, a child care was built, to which the Czech party tied the condition, that the presentations and discussions of the teacher only happen in the Bohemian language, a condition upon which depended the job of the teacher whom I met there. What happened in Pilsen will without doubt also happen elsewhere. Whoever acknowledges the persistent, narrow, shared pursuit of the Slavs, to eradicate the German language in Bohemia, will be forced to admit that this goal will surely be strived for, if very strong and sustainable counter-institutions are not made. (Österreichs innere Politik mit Beziehung auf die Verfassungsfrage, 1847).

In the case of “predominant” meaning “exerting political control or power,” please note that the purkmistr, or mayor of Pilsen for a remarkable 22 years was Martin Kopecký — a Czech — who held office from 1828 to 1850, and who was given particular credit for the furthering of Czech-language education, theatre and concerts there. Considering his position and the length of his career, one might say that he was the town’s predominant figure. Alternately, the era’s predominant personage might have been František Škoda, head of the Pilsen hospital and later the Vienna-appointed head of imperial health services for the region, and one of the twelve signatories of the founding document of the Burghers’ Brewery in 1839.

As for the town being “predominantly German,” Mr. Škoda, born in Pilsen in 1801, recalled that he only learned the German language in school, and only with difficulty, noting that “neither at home nor in the streets did I ever hear a German word.”

“And Pilsen was a town with an influential German-speaking minority and the beer style that had made the town a household name came from a German-owned brewery,” (The Oxford Companion to Beer).

At least The Oxford Companion to Beer got the town’s German-speaking minority right, as opposed to the oft-repeated misconception about the town having had a German (or German-speaking) majority. But in fact, Pilsner Urquell was not “a German-owned brewery.” If you examine the list of the 250 burghers with brewing rights at the time of the brewery’s founding, you’ll see that the vast majority of the names are inarguably Czech: Václav Zdiarský, Jan Kuňovský, Bartoloměj Starý, Karel Dlouhý, Jan Beránek, Kateřina Houska, Martin Kestřánek, and so on, to take names from just one page (source: Měšťanský Pivovar v Plzni 1842–1892). There are some clearly German names in the group as well (e.g., “Majdalena a Anna Gradl,” not “Gradlovy,” one of the rare examples without a Czech feminine ending among the many female names on the list). However, the numbers are not even close. It might have been a mixed group, but Czechs appear to have had a substantial majority, just as they did in the town of Pilsen itself.

That assessment is backed up by the 1916 book Das Böhmische Volk (or “The Czech Nation”), written by a Czech, Zděnek Václav Tobolka. (Again, language does not equal ethnicity: Mr. Tobolka’s tome is a work of strident Czech nationalism, though composed in German.) Here’s how Mr. Tobolka describes the ownership of Pilsner Urquell: “Das Bürgerliche Bräuhaus in Pilsen ist zwar zum grössten Teile in böhmischen Händen, tritt aber immer als utraquistische Unternehmung hervor.”

Alternately put: “The Burghers’ Brewery in Pilsen is indeed largely in Czech hands, though its public image is one of a bilingual [or “bicultural”] enterprise.”

That bilingual façade has fooled many people over the years. However, it should be noted that the town of Pilsen did have a majority-German-owned brewery in the nineteenth century, although it was not the brewery that would come to be called Pilsner Urquell.

As noted by Lauren Stokes at the Besondersweg weblog, one brewery in Pilsen took out “massive newspaper advertisements” in the Dresdner Anzeiger of January 1909, boasting that it was the only brewery in Pilsen that was legally registered in the German language, that its owners were Germans who always voted for the pro-German party, that the brewery’s hotel was frequented only by Germans, with only German-language menus and with only German employees. “The advertisement finishes by promising that the brewery ‘deutsch war und deutsch ist! Und deutsch wird sie bleiben!’,” Lauren Stokes writes.

That is to say, it “was German and is German! And German it will remain!”

That brewery? The Erste Pilsner Aktien-Brauerei, which sold its beer under the decidedly non-Czech “Kaiserquell” brand before switching to its new name, “Gambrinus,” after 1919, and a dedicated antagonist of Pilsner Urquell from the moment it was founded in 1869.

Until it was taken over by Pilsner Urquell in 1932.

Pivní Filosof

I remember reading in Ron’s blog quite awhile ago a mention of a 3.5% ABV Urquell sold in the UK in the 1950’s (more or less). When I asked him about it he said it was a beer Urquell was brewing for the British market.

One silly question, are there any records of the early Pilsner Urquell’s Balling graduation? It’s a well known secret that today’s Urquell is, legally speaking, a 11º.

Another question. How much can the beer have changed after Groll left?

Martyn Cornell

Wonderful, Evan, absolutely wonderful (bows deeply, thrice, in direction of Czech Republic)

Evan Rail

Thanks, Martyn, glad you found it interesting.

I remember reading in Ron’s blog quite awhile ago a mention of a 3.5% ABV Urquell sold in the UK in the 1950′s (more or less). When I asked him about it he said it was a beer Urquell was brewing for the British market.

That’s right, Max, and something similar (currently) in Sweden, too — I used to have a lower-alcohol Swedish can around here somewhere. I wouldn’t be surprised if there are many more beers that were once sold under the Pilsner Urquell brand, and not just during wartime. (At that point, anything goes.) These are non-wartime variations, and in the domestic market, and from the very first year.

One silly question, are there any records of the early Pilsner Urquell’s Balling graduation? It’s a well known secret that today’s Urquell is, legally speaking, a 11º.

Good question. But I think today’s Urquell is just under 12°, and closer to 12° than 11.00°. Jaime’s 2001 example was 11.97°, which we’d have to call a 12°. Things might be the same today, it’d be worth checking.

I’m not sure about the earliest OGs of Urquell back in 1842, as they have not been listed in anything I’ve come across in my research. But we do know they were identified as “výčepní” and “ležák” in Měšťanský Pivovar v Plzni 1842–1892.

Another question. How much can the beer have changed after Groll left?

I’ll leave that for the experts…

Velky Al

Fascinating stuff Evan, especially with regards to the original relation of Gambrinus to Pilsner Urquell, especially as I vaguely recall a comment in your book along the lines Gambrinus being “more a German lager than a Czech one”, I think it was Jan Suran that was quoted – will have to check later.

I am not surprised that Plzen was a predominately Czech town, if I remember rightly there is an early 20th century map of the ethnic makeup of Austro-Hungary which has Plzen in a distinctly Czech area, although not far from the German dominated Sudetenland.

Evan Rail

Thanks, Al. I thought that comment about František Škoda not ever having heard German until he went to school was pretty amazing. And you’re right about the map: Nazi Germany annexed the Sudetenland in 1938, but as I understand it they did not get Pilsen until they took over the rest of the country the next year. Even for the Nazis, it was not possible to argue that Pilsen was German territory.

Now let’s all go have a Kaiserquell.

Mike McG

I’ve been in Prague since the mid-90’s and I’d swear there was a 10° Pilsner Urquell for sale at the time. The bottles were differentiated with silver as opposed to the gold foil. About 8 years ago I did a tour of the brewery and asked about this and was told it certainly didn’t exist.

I wonder…

Barm

I definitely drank a 10º version in the early 90s. I remember because I made a note that I preferred the 12º version.

Velky Al

Mike,

I don’t remember it, but you are right:

http://www.supercollezione.it/wp-content/gallery/repubblica-ceca-3/pilsner-urquell-desitka.jpg

Ron Pattinson

They may not have changed their lagering times after that first brew. Seeing when it was brewed, it’s quite likely that it was a winter beer. Winter beer had a shorter lagering time than summer beer. It could be as little as four weeks:

“Schenk or Winterbier is put into small barrels, holding from 1 to 4 Eimer, Lagerbier or Sommerbier into large barrels holding 20 to 40 Eimer. In the former, secondary, barrel or small fermentation begins immediately, with the latter a bit later. The quicker start of this fermentation in the case of Winterbiers is due to the fact that this is put into barrels, as they say, greener. The bungs are only slightly closed, so that the foam raised by the secondary fermentation can escape. After 8 days, the secondary fermentation of Winterbier is in the main complete, and already perfectly clear; now the bungs are tightened, however the beer still needs to lie for four weeks before being served. Winterbiers intended for later consumption, which have to be lagered longer than one month, the bungs are still not closed tightly at the end of 8 days, but are tightened only 8 days before tapping each individual barrel.”

“Deutsche allgemeine Zeitschrift für die technischen Gewerbe, Volume 2”, page 86. (My translation)

Ron Pattinson

I, too, drank 10º Urquell sometime in the early 1990’s.

Here are some different strength Urquell beers from the 19th century:

1890 Pilsener Exportbier 13.51

1870 Lagerbier 11.91

1870 Export 11.56

1886 Pilsener 10.83

1886 Schenk or Winter Beer 11.20

1887 Lagerbier 11.72

1888 Export 11.95

1898 Export 13.82

Andy Hicks

Evan, were “výčepní” and “ležák” really used as indicators of Balling gravity in the early 19th century? I have always thought that using them in that way was a clumsy, EU-influenced innovation.

Evan Rail

Andy, they were clearly in use by 1892, and as far as I can tell, as early as 1842 if not even earlier. Not EU-influenced nonsense by any means.

Lukas

Karel Knobloch’s tavern couldn’t be “U modré štiky”. In those times was “U modré štiky” well-doing brewery. So they got their own beer not Pilsner Urquell. I’m searching for the right name of tavern in Liliová street, but I still wasn’t lucky.

Evan Rail

Čau Lukáši, thanks for your comment. In Měšťanský Pivovar v Plzni 1842–1892, published in 1892, this is what they wrote:

Tím se stalo, že jěště ve roce, kdy měšťanský pivovar vznikl, několik věder výrobku jeho muselo býti zasláno pražskému hostinskému Karlu Knoblochovi na Starém městě (v liliové ulici), který výtečný ten nápoj poprvé v Praze čepoval a takto do emporia naší milé vlasti uvedl.

The book Plzeňský Prazdroj v historických fotografiích identifies this pub on Liliová street as U Modré Štiky, which of course could be wrong: Karel Knobloch is an interesting figure who had a hand in several beer and brewing businesses in the 19th century — if I’m not mistaken, he is the same Karel Knobloch who bought the Nový pivovar, aka (První) parostrojní pivovar, in Libeň in the year 1880, and who married into the legendary Kašpar brewing family, which owned many brewing enterprises in Prague in the era.

Let me know if you find another pub of his on Liliová ulice that might have stocked Prazdroj in late 1842.

Rod

Congratulations – these three articles add greatly to our knowledge of the early days of Pilsner.

For the record, I also drank 10 degree Pilsner Urquell in the early 90’s in Prague – if memory serves, it was quite comment to find it on draught. I think the Golden Tiger served it?