The influence of Czech brewing often seems surprisingly underappreciated abroad. The great Czech brewing scientist František Ondřej Poupě might have written one of the most important brewing textbooks of the Enlightenment and ranked among the earliest inventors and proponents of the brewing saccharometer, but I’ve rarely, if ever, heard his name mentioned outside of the Czech lands. Similarly, the role that Czech brewers, technology and ingredients have played in global beer culture seems unfairly unrecognized.

I realized this most recently in Belgium, when I was asked to research the history of a large Belgian brewery, during which I spent several days going through some of the remaining archives of a number of Belgian beer makers, including the Brasseries & Malteries Van Tilt Soeurs, the original Hoegaarden brewery, la Brasserie de la Chasse Royale and the old Artois breweries, which took up most of my attention.

What I found serves as a good illustration of how Czech brewing has impacted the beer culture in other countries — without being recognized for doing so.

Long before Stella Artois was first sold in mid-1926, the cutting-edge Artois breweries were highly influenced by Czech beer. Four years before the great Belgian International Exhibition of 1897 — where, in a shock to many local beer makers, one-third of all beer sold was of non-native lager styles like Pilsner, Dunkel and Bock — the Artois breweries were already producing their own bottom-fermented brews.

To do so, the current brewery director Edmund Willems ordered the construction of a new brewery, the Nouvelle Brasserie, to complement the older Artois brewery, Den Horen, which was still turning out the traditional local brews Bière Blanche de Louvain (Leuven white beer) and Peeterman, as well as several other top-fermenting specialties. But in 1893, the Nouvelle Brasserie also started making three kinds of bottom-fermenting Artois beer: Bavière (brewed around 9º Balling, with about 3.4% alcohol), Bock (brewed around 13º Balling, with about 5% alcohol) and Munich (brewed around 14º Balling, with about 5.6% alcohol).

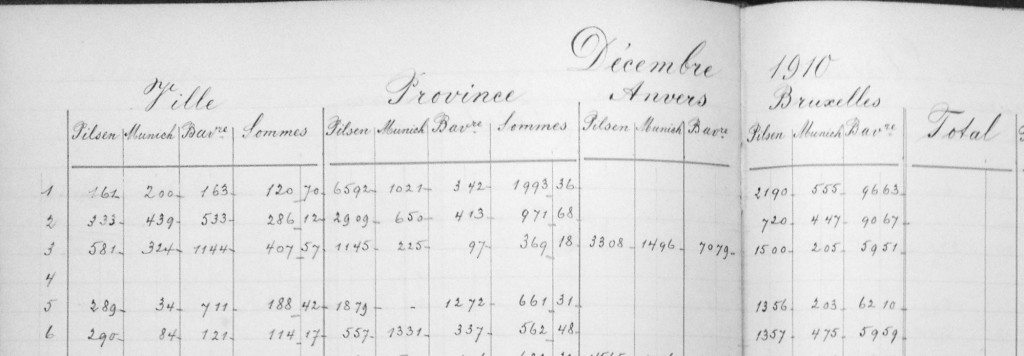

Those names certainly do sound German. However, the brewery’s Bock started to be sold under a more Bohemian name, Pilsen, in October of 1910. This was the exact same beer as the Bock, simply under a different brand, starting with initial sales in Antwerp and Brussels, while in Leuven itself and the surrounding province it was still sold under the Bock monicker for another month or so. By December of 1910, all Artois Bock was being sold as Pilsen.

By the end of 1910 the previous Bock from Artois had been renamed Pilsen.

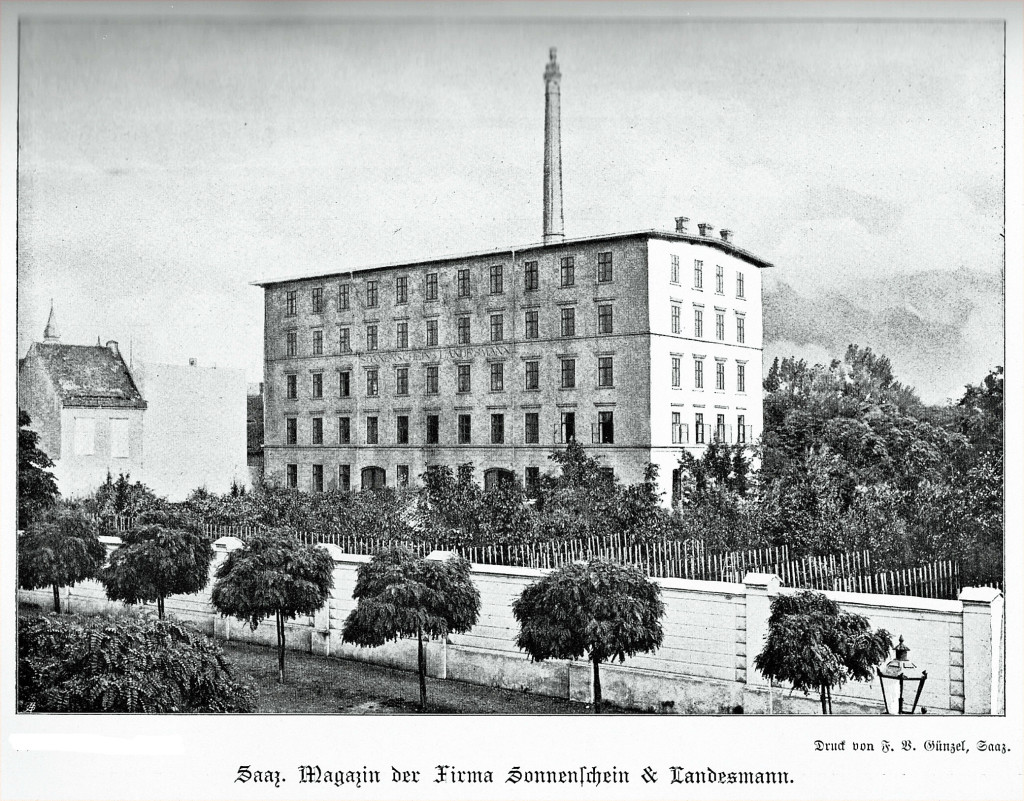

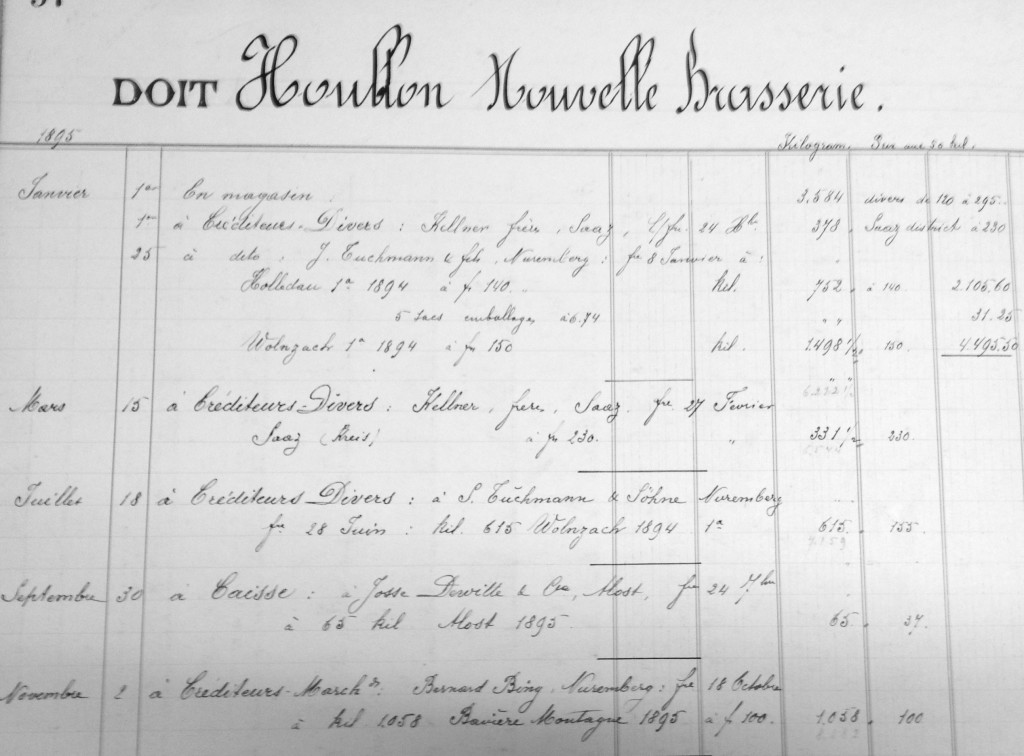

It was not just about the name, of course. To make these new, foreign, even “exotic” beers, the Artois breweries began purchasing ingredients from abroad — by the trainload. For its low-grade Bavière, the brewery used German hops (generally Hallertau, Wolnzach and a less-expensive cultivar, Bavière Montagne), which it bought from J. Tüchmann & Söhne and Bernard Bing in Nuremberg. But for the higher-grade Munich and the Bock that was later renamed Pilsner, the brewery generally used 100% Saaz, purchased from hop vendors like the Kellner brothers and Sonnenschein & Landesmann, both in Žatec (aka Saaz), right here in Bohemia.

The storehouse of the hop vendors Sonnenschein & Landesmann in Žatec (Saaz), Bohemia. Via Wikipedia Commons.

Bohemian hops must have been seen as a very important ingredient, because the amounts the brewery paid for Bohemian hops greatly overshadowed the amounts it spent on German and Belgian hops. In 1895, the Artois breweries paid 230 francs for every 50 kilos of choice Saaz from Bohemia. By contrast, Hallertau (entered in the ledgers as “Holledau”) cost 140 francs per 50 kilos, Wolnzach commanded 150-155 francs, Bavière Montagne cost 100 francs for 50 kilos, while Belgian hops from Alost were just 37 francs for 50 kilos.

In 1896, hop prices seem to have dropped in general, but the difference remained: in the brewery’s accounting books for that year, Hallertau was listed at 95 francs while Saaz cost 125–170 francs. Similar examples can be found in every year up to World War I.

Hop orders for the Artois Nouvelle Brasserie in 1895. The highest prices paid are for Czech Saaz hops.

That added up to some serious cheddar. In 1895, the Artois breweries spent a total of 24,957.71 francs on hops for their new bottom-fermenting brewery (not including the 12,202.20 francs’ worth of hops in the brewery’s storehouse as of January 1). Of that, the lion’s share — 14,208.20 francs — went to the Kellner brothers in Bohemia, 8,586.85 was sent to Tüchmann, 2,116 was paid to Bernard Bing, and just 46.66 francs were spent on Belgian hops used in bottom fermentation.

Despite the higher prices for Czech hops, the brewery clearly preferred them. In 1901, for example, the ratio of kilograms of Czech hops to kilograms of German hops purchased by Artois was more than 3 to 1.

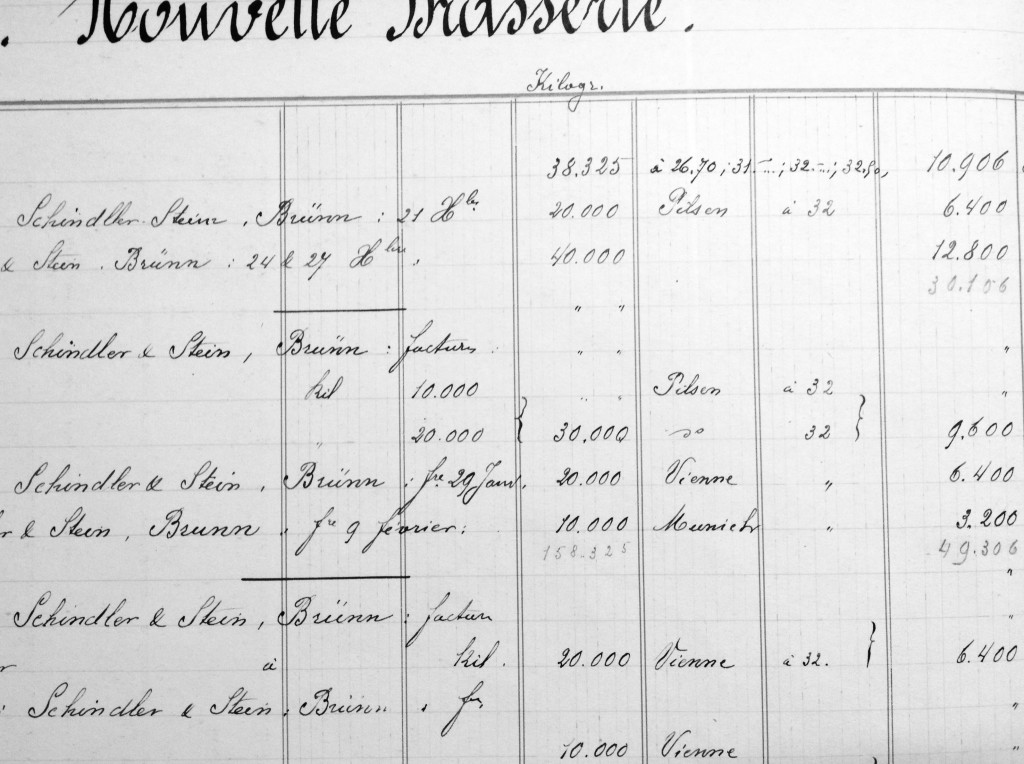

Of course, high-grade hops demand quality malt as well. For their traditional beers, the Artois breweries purchased less-expensive local malt from Belgian malt houses and breweries like Wielemans-Ceuppens, some of which also made its way into the cheaper Bavière. But the higher-grade bottom-fermented brews were given much more expensive malted barley, which Artois imported directly from maltings in what is now the Czech Republic. In 1896, they paid 22.50 centimes for each kilo of Belgian pale malt from Wielemans-Ceuppens, while the price for Pilsner malt they bought from Schindler & Stein in Brno (aka Brünn) was 33.25 centimes per kilo. They also purchased Czech malt from Selikowsky in Litoměřice (Leitmeritz), with whom they appear to have had a very close relationship, and from Hamburger “et fils” in Olomouc (aka Olmütz) — all at higher prices than they were paying for Belgian malt.

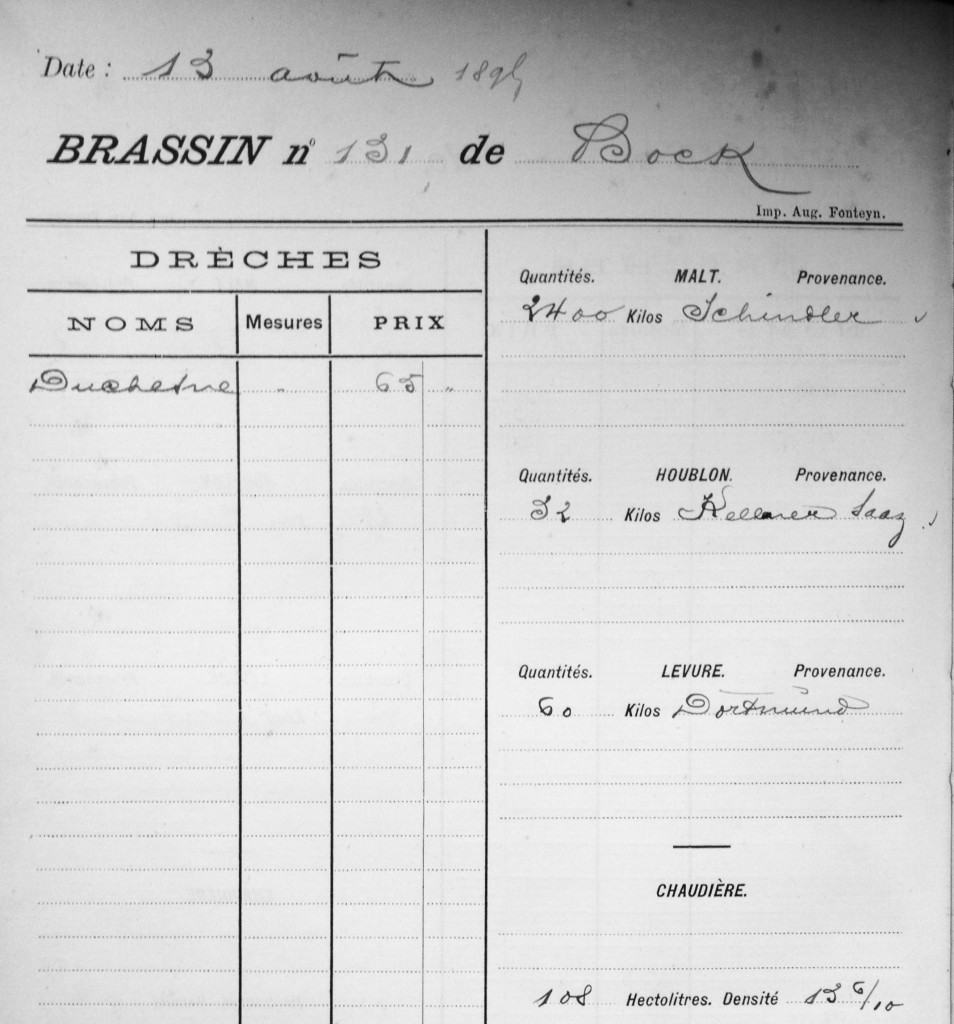

A typical brew of Belgium’s new Bock Artois from 13 August 1895: 100% Pilsner malt from Schindler & Stein in Brno and 100% Saaz hops from the Kellner brothers in Žatec, both of which were imported at considerable expense from the Czech lands.

Interestingly, in that era the brewery was purchasing almost no malt from Germany: the only order I can find was a very small amount of Farbmalz (or “color malt,” roughly akin to Weyermann’s Carafa I today) from Schramm in Munich in one year, and the same from Rübsam in Bamberg in another year. The bulk of all malt used in the brewery’s bottom-fermented beers — including Munich and Vienna malts — came from malt houses in what is now the Czech Republic.

In 1895, the Artois breweries were spending thousands of francs each month on imported Czech malt.

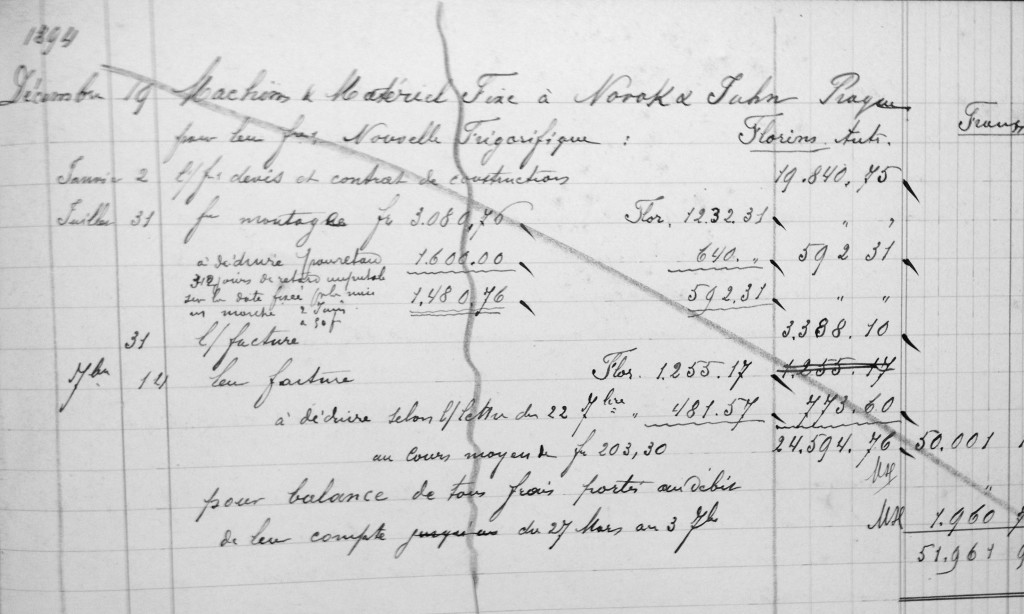

Naturally, if you’re setting up a brand-new, bottom-fermenting brewery, you have to buy new equipment, too. The Artois breweries were not messing around: they wanted the best technology available. That meant Novák & Jahn in Prague.

Accounting for the “nouvelle frigorifique” and other lagering equipment purchased by the Artois breweries from Novák & Jahn in Prague. Prices here are in florins.

(Given the still-pervasive mistaken beliefs about the founders of Pilsner Urquell, it’s worth noting that Novák and Jahn were also not Germans. They were Czechs.)

Of course, if you’re building a newfangled, bottom-fermenting brewery in late-ninetenth-century Belgium and you’re trying to convince the locals that you know what you’re doing, you have to hire new brewers, too.

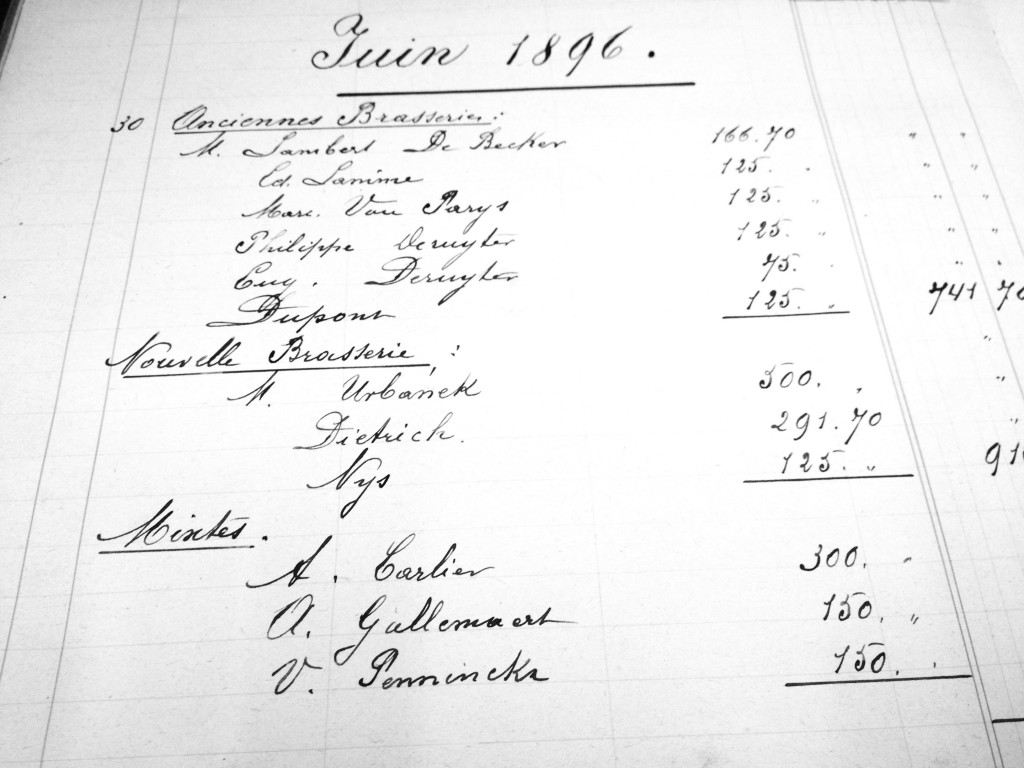

The head of the Nouvelle Brasserie, the new Artois brewery set up in 1893 to produce lagers, was Mr. Urbánek, a brewmaster with a Czech last name and the highest salary of all brewers at the company.

A few observations:

- As brewmaster at the Nouvelle Brasserie, Mr. Urbánek was apparently paid three times as much as Lambert De Becker, the brewmaster at the Anciennes Brasseries, where the brewery’s traditional beers were made.

- Mr. Urbánek’s second at the Nouvelle Brasserie, Mr. Dietrich, also earned more than the brewmaster who making traditional Belgian top-fermented beers for Artois.

- Urbánek is not a Belgian name.

For the moment, this is one illustrative anecdote too far: I haven’t been able to pin down the full identity of the brewmaster at the Artois Nouvelle Brasserie between 1893 and 1896: there is no record of any Urbánek at the city archives in Leuven, and no record of his name at the Rijksarchief in Brussels. The brewery certainly had a penchant for Czech brewing, and Urbánek is most definitely a Czech name. Perhaps I will find his records in the Czech archives someday. But for the moment, Mr. Urbánek might serve as a good metaphor for how the role of Czech brewing is sometimes unknown and unrecognized.

That was not the case among the brewery’s owners, however. The people who ran the Artois breweries had nothing but respect for Czech beer culture — both before the turn of the century, and afterwards.

After World War I, the Artois breweries spent several years in recovery mode, rebuilding damaged facilities, before they began making plans to expand, particularly in terms of lager production. In September of 1931, the Artois brewery’s director general made a grand tour of Europe’s lager homeland, spending three full days (“from 7:30 in the morning until 8 at night”) touring the hopyards and placing orders with the Saaz hop dealers in Žatec. He then went to Prague, where he visited the country’s barley Kooperativa, collecting malt samples. His journey included a number of Czech cities and towns, including Chrudim, Olomouc and Pilsen, whose world-famous brewery he described in a letter back to the Artois brewery as “vraiment incroyable.” (He also went to Munich, where he wrote that the beers were “not great,” noting that the beer from Spaten was “très ordinaire.” He added confidently, “We can certainly do just as well.”)

In his final report to the Artois brewery president, the director general wrote: “Czechoslovakia has really impressed me, the amount of organization achieved by this new republic is really admirable. It’s true that the country has some great natural resources.”

That was hardly news to brewery president Léon Verhelst. Five years earlier, he had led the launch of a new Pilsner-style beer called Stella Artois. Of course, today’s Stella Artois has nothing to do with Czech beer: the recipe for Stella Artois was altered dramatically after its launch. But just as with Artois Bock and Artois Pilsner back before World War I, the initial batches of that beer were once again made with 100% Czech barley and 100% Czech hops.

Note: all of the information, quotes and figures in this post were found in public sources, including the Rijksarchief in Brussels, the Leuven city and state archives, the library of the University of Leuven, and the book “Les présidents des brasseries Artois” by Paul Godaert.

Evan Rail

This story has been a multilingual rabbit hole (Czech, French, German, Flemish) that just keeps on going, currently involving sub-research on medieval art restoration, World War I conscription and 15th-century Bohemian bottom-fermented beers. I hope to have a follow-up in the near future. I’ll try to post more about the old Artois brewing logs soon, including a few more of the 1895–1897 recipes for Bavière, Bock and Munich.

Martyn Cornell

Absolutely fantastic, Evan – a great read. Very much looking forward to reading the botton-fermenting stuff, too. What I’m expecting to see emerge as the final narrative is that brewers were undertaking cold fermentation and cold lagering well before they notice that they now had yeast that settles out at the bottom – unterhefe, or whatever the Czech is – because the successful cross-breeding between Saccharomyces cerevisiae and S eubayanus to make S pastorianus could only have taken place in an environment where chilly fermentation was already taking place, for the new pastorianus yeast to thrive and out-compete the warmth-preferring cerevisiae yeast. But I’m pepared to be wrong …

Jeff Alworth

I wonder how much Czech brewing affected ale brewers. A century later, I found fairly rare use of local hops. Far more common was the use of English hops and Saaz. (There are Belgian-grown versions of English hops, which slightly confuses matters.) The influence of Britain on Belgian brewing is well- (if not completely) documented, and I took hop use as one vestige of it. That might be the case with Saaz as well.

Evan Rail

Interesting observation, Jeff. Saaz was apparently the Citra or Mosaic of its day, at least for lagers, though the Belgian makers of top-fermented brews certainly could have adopted Saaz after British brewers. Ron has some interesting posts about Saaz in British ales:

“Younger’s seem to have had a real thing for Saaz.”

http://barclayperkins.blogspot.cz/2012/02/lets-brew-wednesday-1868-william.html

“Barclay Perkins seemed to like using Saaz for dry-hopping their Strong Ales.”

http://barclayperkins.blogspot.cz/2009/10/dry-hops-for-kk-bott.html