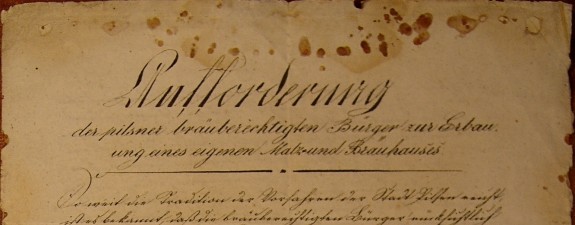

The following is an English translation — by all accounts, the very first — of the original founding document from 1839 of the Burghers’ Brewery in Pilsen, the brewery which would later come to be known as Pilsner Urquell, the world’s first Pilsner beer.

Request of the Burghers with Brewing Rights for the Construction of Their Own Malt- and Brew-house

As far as concerns the tradition of our ancestors in the city of Pilsen, it is generally known that the burghers who held brewing rights lived in constant unrest and tension with the town’s brewers and maltsters regarding the execution of their rights, and certainly not without reason, for there were times when the maltsters and brewers abused the brewing rights for their own profit to such an extent that they often managed to gain them for a bucket of beer or only a few gulden. Thus it happened that the rights fell into complete disrepute.

The burghers of the time felt this pressure from the brewers quite bitterly. Partly because of their excessive goodness, partly because they did not feel strong enough in themselves, they refrained from undertaking anything against these harmful influences, although the means to do so were not unknown to them and — as contemporary witnesses will confirm — already at that time a lively wish to end these circumstances was being heard.

Only in more recent times have our brewing rights begun to be appreciated for their true value and be given their regular appearance. With the belief that these rights have the relevant basis, the burghers’ administration was founded, though it had to be reinforced from time to time, with the purpose of successfully resisting the abuses of the brewers.

That stewardship, elected from within the impartial citizenry, which confronts to a certain extent an excessive means of overproduction, did not function when the brewers assumed the right of setting the price of beer themselves, and so even with the most strict governance it often was not possible to maintain neighborly competition, which had the effect that beer from other dominions was imported into Pilsen and consumed here in significant quantities.

When this contraction was not excessive and the burghers were still enjoying adequate income from their rights, they were content with the referred-to arrangements. But the moment has arrived where their rights are threatened by a much greater danger. Neighboring dominions are attempting to establish storehouses in Pilsen of the very best beer, samples of which have already been officially submitted and which by the current price of barley and malt is being offered at 9 crowns per Maß, therefore 2 crowns cheaper than the price of our local beer. By this a signal would be issued casting the brewing rights of Pilsen burghers the same lot which has already befallen the majority of Czech cities in the same manner.

This danger threatens to the burghers’ right to brew to a full extent and paralyzes the available powers to contradict it. If one such brewery business establishes itself, there is no doubt that it will find many followers, and flood our city with foreign, cheap beer.

Therefore a question is forced upon the interested: in which way could this be prevented, and that the brewing right be endowed with an unmistakable foundation?

The means can be acquired only if the burghers will be able to confront the competition from their neighbors in both the quality and the price of beer, and provide better and cheaper beer to the public.

This cannot be accomplished if current Pilsen brewers endeavor exclusively to enrich themselves at the cost of the public, and not be content if the price of beer rises by one kreuzer per Maß, and for an entire brew by 40 gulden, compared to the prices from our surrounding neighbors; this can only be rectified if the burghers — as has often happened in other towns — construct their own brewery and their own malthouse.

Through such steps would the burghers not not only multiply their production and would obtain for each batch from their own brewery 80 gulden, but also other advantages would accrue to them, namely:

a) there would be gained the savings of rent for the malt house and brewery;

b) all overproduction would be prevented;

c) mature, unspoiled malt would be achieved, and thus

d) the best quality of beer;

e) a burgher, who would brew, would not have to entrust his barley and malt to foreign hands, his capital would not be threatened by fire, etc. — Finally

f) it could improve the quality of the beer by proceeding to produce bottom-fermented beers and lagers, and in so doing the market for Pilsner beer could be gained even outside the territory of Pilsen.

Such an undertaking could be done without problems from the same fund from which the barracks were built and the amount of 24 gulden would remain, which has been paid up until today to the burghers upon commencement of brewing rights, and which would remain untouched. Since the brewing treasury, upon the upcoming initiation of rights, after deducting all obligations, will show significant savings in cash, it could even begin this year.

Since the burghers could build a barracks which cost more than four times one hundred thousand gulden, and then, on the advice of individuals from their own depths make a gift of it, they will certainly not make a mistake when in order to defend the attacks on their rights they will build a malting house and brewery as their own permanent property and an honorable memorial to their descendants.

If some individuals, out of selfishness or unreason, let themselves be seduced into opposition against such a boon, it is to be reminded that such an effort of theirs will be in vain, for a way has been found to accomplish this plan conclusively.

From the Pilsen Burghers Brewing Committee on January 2, 1839.

Evan Rail

This translation was based on the Czech edition of the burghers’ “Request” that appears in Měšťanský Pivovar v Plzni 1842–1892, cross-referenced with a copy of the original, handwritten German-language document from 1839.

Many thanks to Pilsner Urquell for their assistance.